Novelty Detection with Random Network Distillation

“The world is this continually unfolding set of possibilities and opportunities. The tricky thing about life is, on the one hand, having the courage to enter into things that are unfamiliar, but to also have the wisdom to stop exploring when you’ve found something that’s worth sticking around for. That’s true of a place, of a person, of a vocation. The courage of exploring and the commitment to staying — it’s very hard to get the ratio, the balance, of those two things right.” - Sebastian Junger

“To try and fail is at least to learn; to fail to try is to suffer the inestimable loss of what might have been.” - Chester Barnard

We constantly face a dilemma in all aspects of life between exploring the new or sticking with the “tried and true”. Reinforcement learning (RL) agents face the same challenge, often called the exploration / exploitation trade-off. To maximizing expected return, the agent could take the action that experience has shown to be the best. However, trying something new might lead to a better outcome not yet experienced. We can encourage curiosity by engineering an intrinsic reward for novelty to complement the usual environmental rewards. A technique called random network distillation provides an effective way to detect the unfamiliar. Let’s examine the role of exploration, discuss methods for measuring novelty, and build a simple model using MNIST to demonstate novelty detection using random network distillation.

Exploration

Exploration in humans

An inherent tension exists in most of our decisions between exploring the unfamiliar or choosing what we know will produce a good outcome. Should you try a new restaurant or stick with your favorite? Should you spend your evening with the interesting people you recently met, or should you catch up with an old friend? Choosing to explore can lead to finding a new favorite restaurant or meeting that person who becomes a close friend or even life partner. Should we “step outside our comfort zone” or “stick with what we know”?

Across a human life, exploration dominates the first half. Infants explore their range of motion while learning to walk. They indiscriminately put objects in their mouth, much to the chagrin of parents. Growing up involves experimentation and failure, trying new hobbies and professional endeavors until the ones worth pursuing become apparent.

During the later phase of life when our finite time horizon becomes more apparent, exploiting our accumulated knowledge makes more sense. We invest increasing time in the people and activities we love. And although a new discovery still brings delight, we have less time to enjoy and make the most of it.

Exploration in reinforcement learning agents

Exploration helps RL agents gather information. Much like a child, an agent has limited experience early on and lacks the breadth of knowledge to choose good actions. A basic approach called $\epsilon$-greedy involves taking a random action some percentage $\epsilon$ of the time to ensure exploration. The rest of the time, the agent takes the best (greedy) action based on experience. $\epsilon$ can decrease over time, for example through annealing, to favor more exploitation as the agent gains experience.

In environments with sparse rewards, the agent receives less feedback on what actions are good. Random actions, even if taken 100% of the time, might lead an agent to run around in familiar circles without learning. The agent needs to explore and seek out new experiences to find a useful reward signal for guidance. Moreover, sparse reward environments are more representative of the real world. Our environments often give a singular reward for accomplishing a goal. The absence of intermediate rewards to help guide the way highlights the importance of intrinsic motivation.

Even with dense rewards, environments that are complex, dynamic, and long or indefinite in duration make exploration crucial. The agent cannot rely on exploiting gained knowledge in the presence of significant change, especially when much more time lies ahead. An agent that doesn’t explore enough faces the risk of learning a suboptimal policy. It might get stuck collecting small rewards in one part of an environment, not knowing much better rewards exist elsewhere. An intrinsic bonus for novelty creates a willingness to explore the environment and potentially discover more rewarding experiences.

Measuring novelty

Counting visits

One way of measuring novelty is counting state visitations. A discrete state space allows easy counting of how many times a state has been seen. We can then formulate a novelty metric inversely proportional to the number of visits. States with less or no visits receive a higher novelty reward than familiar states with many visits. Environments with a continuous state space wouldn’t work well with such an approach, since most states would only be seen at most once.

Prediction error

Prediction error is another way to measure novelty. We can predict the familiar with more accuracy than the unfamiliar. Consider a forward dynamics model predicting the next state based on the current state and action. Also consider some state and action pair that often leads to the same subsequent state. Upon seeing the familiar state and action as input, the model would predict the familiar subsequent state as ouput. If that familiar subsequent state indeed follows, the prediction was good and error is low. However, if the transition probability function of the environment produces an unexpected subsequent state, the prediction error would be high. Rewarding high prediction error produces a curious agent drawn to unfamiliar states.

Environmental sources of stochasticity — sometimes called the noisy TV problem — can present a challenge for methods based on prediction error. Consider again using a forward dynamics model for prediction error. A stochastic source in the environment like a TV displaying noisy static results in high prediction error. The forward dynamics model cannot predict the next state of the noisy TV because the static is random. The curious agent inteprets the high prediction error as novelty and can get stuck staring at the TV! Check out the paper by Burda, Edwards, Pathak et al. titled “Large-scale study of curiosity-driven learning” for more information.

Random Network Distillation

Burda, Edwards et al. introduced another approach for detecting novelty in the paper “Exploration by random network distillation” (RND). While also based on prediction error, RND aims to predict a deterministic function, precluding issues with stochastic dynamics and avoiding the noisy TV problem. The deterministic function is a neural net taking state observation inputs. The network parameters are randomly initialized and fixed. Let’s call this the Target Net.

RND trains a second neural net with the same architecture (but separate initialization) to predict the output of the Target Net. Let’s call this the Predictor Net. For familiar observations, the Predictor Net has a good idea (low error) of what the Target Net will output. Conversely, a high prediction error indicates a novel or less familiar observation. Moreover, regardless of randomness in the input observations (e.g. noisy TV), the Target Net outputs are a deterministic function of the inputs. The Predictor Net only predicts the Target Net’s deterministic output given common input observations, without dealing with potential stochastic dynamics.

Distillation

Distillation refers to transferring knowledge from one model to another, usually as a form of model compression where the distilled model is much smaller while retaining comparable predictive power. Hinton, Vinyals, and Dean wrote a paper called “Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network” where they transfer the knowledge from a large neural net or an ensemble of models into a smaller neural net.

Hinton et al. point out much of the knowledge in a neural net classifier resides in the relative probabilities of the incorrect classes. For example, how much is the second best answer better than the third best, or the fourth best? However, classifiers are trained to maximize the probability of the correct class. After passing through the softmax function, the incorrect class probabilities get squashed down to near zero. Hinton et al. add a “temperature” parameter $T$ into the softmax function to produce “soft” targets with a softer class probability distribution to retain more of the useful knowledge present in the logits:

The correct class still retains the highest probability, but the relative probabilities of the incorrect classes become more apparent with increasing temperature. The distilled network is trained on these knowledge-rich soft targets, producing a smaller model with predictive power comparable to the large model. The distilled model learns to generalize much better than had it been trained on the same data as the large model using ground truth targets.

In RND, both the original target network and distilled predictor network are the same size. We use distillation to transfer the “knowledge” — the mapping between input and output vectors — from the Target Net to the Predictor Net. We train the Predictor Net parameters by minimizing the mean squared error between the Target Net and Predictor Net outputs. The parameters of the Target Net remain fixed after random initialization. The actual output and “knowledge” of the Target Net aren’t particularly useful in isolation. Rather, the error between target and predictor, given common observation inputs, provides a relative measure of novelty across observations. And unless the target and predictor network parameters are identical, some useful error will inevitably exist.

Novelty detection experiment

The RND paper introduces a simple model using the MNIST dataset to demonstrate novelty detection. Let’s reproduce that experiment to show the relationship between observation novelty and prediction error.

Constructing a two-class dataset

MNIST contains a total of 70,000 images, with each of the ten digit classes have ~5000 images in a training set, ~1000 in a validation set, and another ~1000 in a testing set.

We construct a two-class dataset where one class represents familiar observations and the other represents novel or less familiar observations. Using images of handwritten digits from MNIST, images of zero will compose the majority of the dataset and represent familiar observations given their prevalence. We then choose one of the non-zero classes to represent novel or less common observations. We control the degree of novelty by varying the percentage of the non-zero class present in the dataset. For example, novelty is high if only a few images of the non-zero class are present. Conversely, if several hundred samples of the non-zero class exist in the dataset, that class becomes much more familiar. The overall number of samples in the dataset remains constant.

Target and predictor networks

In the RND paper, the target and predictor networks use the same architecture as the policy network. For benchmark Atari environments like Montezuma’s Revenge, this consist of passing pixel inputs to convolutional layers, followed by fully connected layers, before an output layer sized according to the action space. For our simpler model using MNIST image inputs, we can use any architecture capable of good predictions on MNIST. For example, a simple neural net with a single hidden layer or a small convolutional neural network (CNN) can attain high accuracy on MNIST. We randomly initialize the network parameters for the Target Net and keep them fixed. The Predictor Net uses the same architecture with separately initialized parameters — don’t use the same initial parameters as the Target Net or the prediction error will be zero.

Training the predictor network

With the Target Net parameters fixed, we train the Predictor Net to approximate the mapping in the Target Net. To get targets for training the Predictor Net, we do a forward pass of our two-class dataset through the Target Net. We also remove the usual softmax layer and train on the raw network outputs (logits). Training a classifier typically requires a softmax layer to convert the logits into a class probability distribution. However, as mentioned in the distillation section above, the softmax squashes the incorrect class probabilities down toward zero. To get more information in the network outputs, we train directly on the logits. We train the Predictor Net by minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) between its outputs and the targets obtained from the forward pass through the Target Net.

Calculating prediction error

What exactly does the relationship between novelty and prediction error look like? To produce a useful instrinic reward, we need a way to measure the relative novelty between observations. Conceptually, our Predictor Net should perform well (low error) at predicting the Target Net output given familar observations. For unfamiliar observations, the Predictor Net hasn’t learned what the Target Net will output, thus producing higher error. Let’s calculate prediction error across datasets with varying novelty.

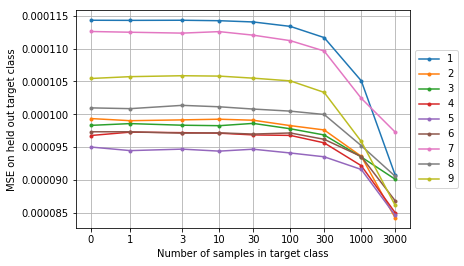

We adjust novelty in our dataset by varying the composition of the non-zero class, essentially assembling a new training set each time. For each dataset composition, we train the Predictor Net on the outputs of the Target Net and calculate MSE on samples of the non-zero class from a held out test set. We can perform this experiement across all nine non-zero digit classes.

Importantly, because the prediction error is a relative measure across observations and also a function of the initial network parameters, all experiments (both across novelty percentage and across non-zero class) should start from the same Target Net and Predictor Net initial parameters. We generate initial parameters for each of the two networks, save them, and reload them for each experiment.

Relationship between prediction error and novelty

As we vary the occurrence of the non-zero class in the dataset to vary novelty, we see the prediction error (MSE) drops with increasing occurrence. The more familiar the non-zero class is, the lower the prediction error. The same behavior occurs regardless of which digit we use for the non-zero class. This demonstrates prediction error from random network distillation can produce a novelty signal useful as an instrinic reward to encourage exploration.